- Posted on:July 14, 2024

- Categories: History

- Author: Darren Sapp

After several days of hard riding, the posse cornered the bandits that attempted to rob the bank at Northfield, Minnesota. Concealing themselves behind heavy brush and trees, the outlaws refused to surrender. A gunfight ensued killing one bandit, disabling two others, and leaving one, Bob Younger, with the ability to stand and offer an, “I surrender.” Just as he said that, a shot entered his chest. The posse descended on the battered group, which revealed three starved, exhausted survivors. As the posse helped the outlaws to a wagon for transport to town, they learned that part of the group escaped. They killed Charlie Pitts, Bob Younger suffered from the chest wound and shattered elbow, Jim Younger had a horrific wound from a bullet lodged inside his upper cheek, and Cole Younger held eleven new bullets in his body. But what happened to the more famous Frank and Jesse James?

One week earlier, eight men rode into Northfield, Minnesota to rob the bank, but instead faced numerous townspeople who quickly assembled with rifles, having prepared for just such an occasion. Catching the bank robbers off guard, hundreds of bullets flew through the air for approximately ten minutes. Two of the bandits lay dead, Clell Miller and Bill Chadwell, with six others escaping on horseback. One of the bandits shot bank teller Joseph Lee Heywood inside the bank and innocent bystander Nicolas Gustavson fell dead due to an errant bullet. Authorities quickly resolved that this was the work of the James-Younger gang that terrorized the Missouri-Kansas region for a decade following the Civil War. Most of the gang consisted of former Confederate guerilla fighters who continued their reign of violence, looting, and robbing since the war’s end. Were they victims of Northern aggression or Confederate opportunists?

With the capture of a portion of the gang, the authorities, as well as the public, first learned of the dynamics of the outlaw band. One outlaw, and in essence the only one willing to talk, Cole Younger, emerged as a larger-than-life figure. Several years later, a ballad written about him contained lyrics such as:

“I am a bandit highwayman, Cole Younger is my name.

In many a desperation I’ve brought my friends to shame.

For the robbing of those Northern banks is such I can’t deny;

And now I am a poor pris’ner—Stillwater jail I lie.”[i]

Was this ballad accurate? Were the numerous dime novels written about him and the James brothers true? Thomas Coleman (Cole) Younger (1844-1916), the less famous “leader” of the James-Younger gang, represents a prime example of the young men who struggled through the sectional crisis of the 1860s so close to home. For a Southerner in Missouri, the enemy came painfully close, sometimes as close as their own backyard. Following the murder of his pro-Union father, supposedly by Union soldiers, young Cole evolved from soldier to guerilla to bandit to prisoner to businessman.

The Kansas-Missouri border presented a unique example of sectional conflicts within counties, towns, and even families. Cole Younger’s simple teen years were disrupted at the onset of the war, forcing him to choose a side, leading to guerilla warfare and a life on the run. Under reconstruction, he found little peace as many wanted to hold him accountable for his actions during the war. He chose to remain on the run, acting upon his guerilla training and participating in numerous robberies with other guerilla veterans. All of this came to an end in 1876 with his capture at Northfield and sentence of life in prison.

Authors and journalists found it difficult to tell his story for many years because he, like other guerillas and fellow bandits, refused to tell the entire truth, fearing retribution for past crimes from guerilla actions. As late as the 1920s, many interested parties sought deathbed confessions from them. With the exception of confiding in two close friends shortly before his death, Cole Younger never acknowledged that Frank and Jesse James joined him at Northfield, referring to them as Howard and Woods, their known aliases. Younger never admitted to any crime other than Northfield. The folklore surrounding him made the task even more difficult. Was Younger the father of Belle Starr’s daughter? Did he really line up several Union prisoners to see if a new type of rifle could shoot through several of them? Was he in a constant power struggle for leadership within the gang?

Those questions aside, a comparison of sources such as printed works, interviews, newspaper articles, and official records reveals most of his story. Younger’s personal conversion from criminal to peaceful citizen reveals a repentant man who slowly dispelled the inaccuracies about his life. While the titillating details of bank, train, and stagecoach robberies remain difficult to discern, his life leading up to the period is much clearer. His statements and well-documented guerrilla actions coincide with great frequency.

Sectional Strife

The images of Atlanta following Sherman’s march to the sea show scorched earth, but the Missouri-Kansas region experienced its own destruction during the Civil War. As the Kansas territory entered the statehood process, the question of its admission into the Union as a slave or free state remained a decision for voters in the pending state. Missouri, a slave state, desired to border Kansas, also a slave state, for economic and political reasons. Several people crossed over from Missouri to Kansas to skew the election to vote for slavery. These “border ruffians” as many called them clashed with anti-slavery forces known as Jayhawkers. These skirmishes spread throughout the region and a full border war erupted, leading to the occupation of Missouri by Northern troops.[ii]

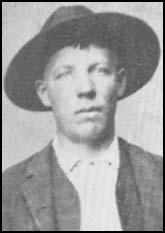

A young Cole Younger.

Young, male Missourians made the difficult decision of whether to join the State Militia, enlist in the Confederate army, or join one of the many small bands of guerilla fighters. Most of them lumped into two distinct groups; the anti-slave pro-Union Kansas Jayhawkers and the pro-slavery Bushwackers for the Confederacy. An ambiguity existed in the relationship between each of these groups and their official military counterparts. Jayhawkers typically followed the orders of their leaders in Washington, although President Lincoln distanced himself from their extreme actions. Confederate President Jefferson Davis held a tenuous relationship with the Bushwackers. While he could not control them and did not condone all of their actions, he appreciated that these small bands of guerrillas kept tens of thousands of Northern troops occupied in Missouri.

Henry Washington Younger settled in Clay County, Missouri with his wife Bursheba and fourteen children during the antebellum period. He developed a successful livery business in addition to mail delivery and dry goods distribution. The elder Younger, a moderately pro-Union slave owner, hoped his family would work through the sectional strife and eventually return to life as normal. Second oldest son Coleman experienced much of his father’s difficulties from pro-Union Jayhawkers looting his possessions. The next three boys, James (Jim), John, and Robert (Bob)—all too young to respond to the growing crises—suffered the Jayhawker’s terror as well.

While in prison, interviewer J.W. Buel asked Cole Younger what caused the guerillas in Missouri to rise up. He responded that “this diabolical war, distinguished by the most atrocious cruelties the conqueror can inflict upon his captive, prepared the way, and created the guerilla in 1862.”[iii] Unionists forced Missourians to decide which side they supported at the beginning of the war—an occasionally fatal decision. His father’s death in 1862 was not the sole reason for his decision to fight for the South, but it certainly served as the catalyst for his anti-Union fervor. Cole joined the infamous band of guerillas under William Quantrill.

In the fall of 1861, Cole had an altercation with a Union officer named Irving Walley over his advances on Cole’s sister. Walley tried to have Cole arrested as a Quantrill spy, but Cole evaded capture. In June of the next year, Cole’s father traveled for a business trip when a group of men shot him to death. Stories vary, but most conclude that a band of Union soldiers, presumably led by Walley, killed Henry Younger in retribution against Cole Younger.[iv] It is uncertain whether Walley and his group committed this act, but Cole Younger believed they did, and his hatred for pro-Union forces now held no bounds. If he ever felt any ambivalence over participation in guerilla acts, those feelings left him. He pledged his loyalty as a fully-participating Quantrill guerilla.

William Quantrill’s background does not lend itself to someone who would become the most famous leader of the Confederate guerilla forces. Raised in the North, he had previously held occupations such as farmer and teacher. Through various relationships during the Kansas-Missouri border conflict, he helped sabotage a group of abolitionists trying to free slaves. After learning proficiencies in firearms, he developed a cult following and organized a group to carry out similar acts against abolitionist forces.[v] His group numbered over one hundred, causing numerous problems for Union forces. Similar groups led by “Bloody” Bill Anderson and George Todd, along with Quantrill, created havoc across Missouri and Kansas. Union military leaders attempted various means to control the guerillas but found their network too strong to overcome.

Cole Younger serves as an example of how guerilla soldiers operated. He could fight in a small skirmish or perform an act of pillaging, then escape several miles on horseback. A string of neighbors and relatives would provide places to hide, fresh horses, food, and alibis. If injured, a doctor, sympathetic to the cause, would gladly give him care and then send him back into the field with fresh supplies. Union Brigadier General Ben Loan wrote an official report to Major General Samuel R. Curtis on the situation in November 1862. He stated that “such bands as Quantrill’s find a market for their stolen property” and that “I think have driven the Bushwackers out of the country, but they will return immediately.”[vi] Numerous official records exist bearing the same situation. Northern forces found it extremely difficult to control guerilla activity due to the deep sympathies of the local population toward the guerillas.

Known as a family to be protected, and one that would protect others, the Younger family fully supported the Southern cause. The youngest boys, John and Bob, sought to join the guerillas, but the family farm needed their attention. Seventeen-year-old brother Jim joined the guerilla forces led by George Todd. Cole, however, made a name for himself as a capable fighter. The Story of Cole Younger, by Himself—an autobiography written by Cole Younger—sought to dispel many of the myths about him. While he goes to great lengths to offer alibis for various crimes, a great portion of the book deals with his time in the guerilla forces. One does not find self-aggrandizement or an overstatement of his service. Rather, he offers a methodical account of his actions as a soldier and presents these accounts as his duty. Whether an official record or current non-fiction work on Cole Younger, all agree with his autobiography regarding his abilities as a soldier and that he never engaged in any gratuitous killing.

That said, he and many others acknowledge his active participation in the massacre of Lawrence, Kansas. Quantrill’s raid on this town carried a somewhat strategic purpose, but vengeance motivated the action. General James Lane—the hated leader of the Kansas Jayhawkers—called Lawrence his hometown. The plan called for a complete sacking of the town. Surprised by the well-coordinated attack, the town offered little defense. Killing nearly every male, the guerillas burned several buildings. The main target of the attack, General Lane, survived by hiding in a cornfield. Several accounts suggest that Cole saved many lives by showing quarter to defenseless victims. This event may have caused Cole to reconsider the guerilla lifestyle and whether his nature tolerated their methods.

Quantrill’s accomplice, “Bloody” Bill Anderson, led his own massacre at Centralia, Missouri one year later. A guerrilla named Jesse James gleefully took part in those killings. The Anderson, James, and Younger families had all suffered terribly during the war. The Union forces began a campaign to reign in the guerillas through their families. After confiscating and burning many of the guerilla’s farms, they arrested and imprisoned many of the female members of their families on the charge of aiding the guerillas. One of the prisons collapsed, killing some of the women, including Bill Anderson’s sister. This event likely caused Anderson to earn his nickname “Bloody” as he sought revenge. The Younger sisters escaped harm but had suffered from their eviction and were forced to watch their home burn. Following this event, Cole Younger seems to have entered a period of peace seeking a more effective use of his talents to win the war.

He joined the regular Confederate army in the waning days of the conflict, performing non-combat duties. He may have reasoned he would escape the repercussions that awaited captured guerilla veterans. Returning home to Lees Summit, Missouri, he found anything but life returning to normal. The Younger family hoped to revive their father’s business and restore the family’s upper middle class fortune. Confederate supporters earned a parole of sorts if they took a loyalty oath.[vii] Jim Younger, a veteran guerilla under Quantrill and Todd, signed the loyalty oath, seeking release from a military prison. Cole’s reputation prevented him from signing the oath. No oath would pardon his “crimes” against the Union. His return to the life in Missouri he had known before the war seemed improbable. Life under Reconstruction for the Younger family proved extremely difficult.

Life of Crime

Southerners had little recourse under Reconstruction. They simply had to bear the consequences of losing the war. Reconstruction plans by those in the North generally fell under three categories. The moderate view involved rebuilding the physical South, support of the freedmen, and restoration of the Union. A somewhat tougher view—that of the Radical Republicans—did not go so far as to punish the South, but wanted to ensure that rebellion could not happen again. The extreme view, although not official policy, required punishment and retribution. This latter view was the one experienced realistically, or at least seemingly, by many ex-guerilla fighters such as the Younger family and two brothers, Frank and Jesse James.

Frank James and Cole Younger had developed a friendship while serving together under Quantrill. Cole would not meet Jesse James until 1866. In that same year, the first daylight bank robbery took place on February 13 in Liberty, Missouri. The new gang supposedly chose this bank because it held Yankee money, the reason for many of the robberies.[viii] Thus began a near ten-year period of robberies of banks, trains, stagecoaches, and fairs. Many outlaws participated in just one or two crimes, but the core three were Cole Younger, Frank James, and Jesse James.

Jim Younger floated in and out for various robberies, but typically avoided them when he could. Little brother John Younger sought the life of crime and asked to join the bandits, but it is unclear whether he participated in any robberies. A list of nearly 25 other names can be linked with the gang, most of them ex-guerillas.

For all the bank, train, and stagecoach robberies, Jesse never stood trial, and Frank, although tried many times, never received a conviction. Everyone knew that the James-Younger gang committed most of the crimes, but the authorities found it difficult to prove. While journalists incorrectly attributed additional robberies to them, Jesse James boldly claimed responsibility for some and wrote letters to newspaper editors correcting them on their stories, bolstering his folk legend. Their reputation as “Robin Hoods“ gained momentum. Similar to their time as guerillas, they found no shortage of friends willing to harbor them during these escapades. This made their capture extremely difficult. The Pinkerton detective agency, eventually hired to capture the gang, harassed the gang’s friends and family, similar to the way Union forces harassed the guerillas.

Life as an outlaw mirrored that of a guerilla. They could never stay in one location too long. Around 1870, the Younger family, including their mother and sisters, moved to Scyene, Texas, south of Dallas. North Texas towns such as Bonham and Paris provided safe havens for guerillas during the war. With little news of their notoriety in Texas, they lived peacefully and held honest jobs. In Scyene, Cole met and held some sort of relationship with Myra Shirley—later known as Belle Starr. He denied that he ever fathered a child with Belle, but Belle’s daughter used the name Pearl Younger for some time. While somewhat titillating, the Belle Starr connection to Cole appears to have been brief and insignificant. A general restlessness for home set over the Younger family. John Younger revealed a reckless side; for this and various other reasons, the family returned to Missouri.

Over the next few years, the gang conducted several profitable robberies, many without incident to outlaw or bystander. However, Jim and John Younger engaged in a gunfight with two law enforcement officers, killing John. Another deadly incident occurred when Pinkerton detectives threw an incendiary device into the James’ home. An explosion killed Frank and Jesse’s half-brother Archie, and their mother lost her arm. These incidents only bolstered sympathies for the gang. Although never an overtly murderous band, innocents did die, but typically by accident.

The gang decided to rob the bank in Northfield, Minnesota, believing it held a large amount of “Yankee” money. This job required elaborate planning and involved a long excursion. The gang traveled to Northfield in several groups, some scouting the location while others secured horses and established escape routes. No one in the gang knew the geography of the area. On September 7, 1876, they rode into town unaware that the Pinkertons had warned the town that the James-Younger gang likely targeted their bank. In addition to the James and Younger brothers, gang veterans Bill Chadwell, Charlie Pitts, and Clell Miller rode along.

Inside the bank, the teller informed the bandits that the safe had a time lock that could only open at a certain time. Outside the bank, bandits prevented townsfolk from going into the bank. The extended time arguing with the teller and the disruption outside signaled the town of a hold-up in progress. Several men grabbed their rifles and a massive gunfight ensued, killing bandits Miller and Chadwell while the other six escaped. All but Jesse James received wounds and Bob Younger suffered from a shattered right elbow, bleeding profusely. With little knowledge of the terrain, no support network of friends to harbor them, and their wounds slowing them down, they made little progress in their escape. Mutually deciding that the James brothers would separate from the group, the Younger brothers stayed together along with Charlie Pitts, who could not have kept up with the Jameses due to his injuries. Their capture occurred shortly thereafter, approximately 80 miles west of Northfield, near Madelia, MN.

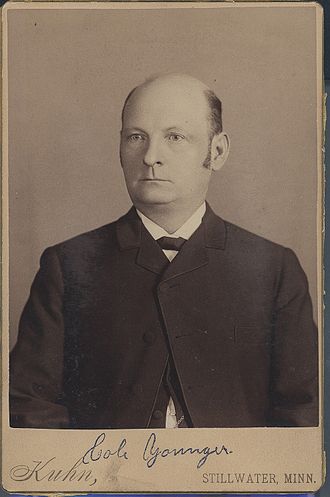

Cole Younger mugshot.

A Different Life

The minor outlaw celebrities arrived in town in pitiful shape, except for Pitts who died in the woods. All of them suffered from significant injuries. Jim—plagued by his mouth wound— never again ate solid food. All three pleaded guilty to avoid hanging and received life sentences in Stillwater prison. Assuming they would earn parole in as little as five years, they settled into prison life as model prisoners and entertained several visitors. In an 1880 interview, Cole avoided questions connecting him to other bandits, such as the James brothers, presumably to protect Frank.[ix] Several friends wrote letters to the state seeking their pardon. Bob Younger died of tuberculosis in 1889, partially attributed to the chest wound he suffered after Northfield. Finally, twenty-five years into their sentence, Cole and Jim Younger received conditional pardons in 1901, and began working various jobs in Minnesota. Jim, depressed that he could not marry a woman he loved, committed suicide in 1902. Ironically, he did not want to participate in the Northfield robbery, but did so reluctantly, at Cole’s urging.

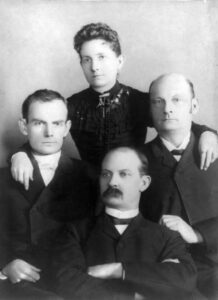

Cole Younger with brother Bob (left), brother Jim (bottom) and sister Henrietta.

Cole’s parole prohibited him from participation in any type of show or exhibition charging money, and kept him, in his opinion, from earning a proper living. The Cole Younger and Frank James Wild West show violated his parole, but since the show only lasted a short time, authorities never charged him with parole violation. He received extended parole in 1903 allowing his return to Missouri. He spoke at many public venues with a speech entitled, “What Life has Taught Me,” where he denounced his outlaw life and extolled the virtues of Christianity. His life following the shootout near Northfield had been one of quiet and peace until his death in 1916, just one year after the death of his friend Frank James. He supposedly carried seventeen bullets with him into death, evidence of a violent life.

Cole’s use of the term “raid” to describe the robbery at Northfield speaks volumes to his attitude. He seemed to view the robberies as a raid similar to the raids he and his fellow guerillas conducted during the war. The Civil War, and in particular the Kansas-Missouri border war, produced the guerilla fighter Cole Younger. It remains a difficult task for anyone today to assume that he could have easily settled into a peaceful life following the war. While victim status perhaps overreaches, no evidence suggests he took advantage of his situation for mere sport or economic reasons. One could argue that the proper response for all of the guerilla fighters should have been to enlist in the regular Confederate army.

Regardless, Cole Younger found peaceful life difficult following the war. After his years in prison, he slowly revealed a general repentance for his past. Although never admitting to the many specific crimes attributed to him, he certainly acknowledged a criminal past and sought forgiveness. Neither term, “victim” nor “opportunist,” seems a proper fit for Cole Younger. Many agree that raids conducted as a guerilla violated the rules of war, and raids conducted as a bandit violated the rule of law. The difference in tolerating the raids depends upon one’s Union or Confederate perspective. One word for Cole Younger certainly fits—outlaw.

[i] John Q. Anderson, “Another Variant of ‘Cole Younger’, Ballad of a Badman.” Western Folklore 31, no. 2 (April, 1972): 104.

[ii] Richard S. Brownlee, Grey Ghosts of the Confederacy. (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1986), 7.

[iii] J.W. Buel, “A Personal Interview with Cole Younger,” Civil War St. Louis, http://www.civilwarstlouis.com/History2/jamescoleinterview.htm (accessed October 29, 2009).

[iv] Marley Brant, The Outlaw Youngers: A Confederate Brotherhood. (Lanham, MD: Madison Books, 1992), 29.

[v] Brownlee, 57.

[vi] The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies, Series 1, Vol. XIII, 806-07, Letter from Brigadier General Ben Loan to Major General Samuel R. Curtis, 1862, Columbus, OH: Ohio State University Department of History ehistory Collection, http://ehistory.osu.edu/osu/sources/records/ (accessed November 21, 2009).

[vii] Brant, 63.

[viii] Ibid, 73.

[ix] “An Old Accomplice’s Comment: An Interview with Cole Younger, in Jail in Minnesota,” The New York Times, 5 April 1885, p. 5.